El legado vivo de Hugo Blanco indispensable aquí y ahora

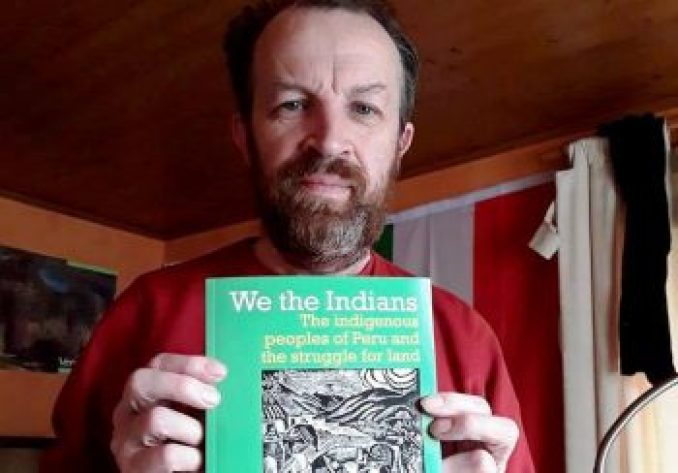

La Voz de Perú traduce un texto del Profesor Andrew Ryder sobre Hugo Blanco Galdos que compartimos también en su versión original en inglés. Hugo debería haber hablado en Londres el 6 de noviembre de 2018 para presentar su libro «Nosotros los Indios» en inglés, pero, a pesar de haber presentado la solicitud de visa a tiempo y de haber estado en varias ocasiones en el Reino Unido, lo cuestionaron por haber sido prisionero del régimen Peruano en el pasado y realizaron maniobras burocráticas de modo que la visa fue expedida cuando ya le era imposible viajar. Estará en Manchester el 25 de febrero próximo.

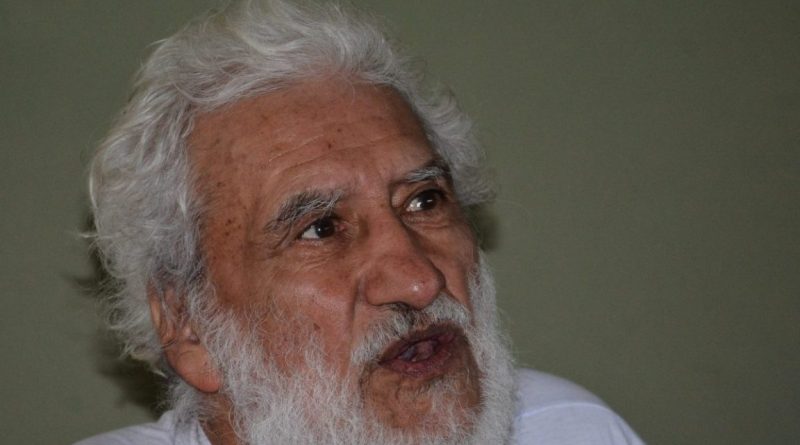

«Mi legado ha comenzado a caminar» afirmó el propio Hugo hace poco. El Legado vivo de Hugo Blanco Galdos viene tejiéndose desde México y va entrando desde abajo, con la tierra y a la izquierda dondequiera que luchan los pueblos e individuos. El texto de Ryder expone lo que alcanza de la trayectoria revolucionaria de este revolucionario perenne. Hugo se sometió él mismo a la revolución varias veces y lo hace ahora a diario. Esa guerra interna contra nuestra mentalidad capturada y sometida bajo toda clase de discursos y prácticas, es el corazón, el alma y la fuerza de la revolución. Actuar con coherencia y compromiso arriesgándolo y entregándolo todo, claro. Pero además y ante todo, examinar palabra y acción para reconocer constantemente aprendiendo en un «régimen de verdad» ese enemigo que nos penetra y habita, esa Hidra, como la señalaran las y los zapatistas y cuestionar en consecuencia las propias prácticas, convicciones y caminos. Hugo lo hizo, lo hace, aprendió a hacerlo y por ello su legado vivo no es del pasado y tiene una vigencia que nos reclama y nos ayuda en este contexto de neo-fascismo de todas las pelambres, con todas las máscaras. Hoy, mientras nos someten, engañan, amenazan, reclutan y compran a nombre de todo, Hugo Blanco Galdos tiene una vida para sostener que un revolucionario no se vende, no se cansa, no engaña ni se deja engañar y ante todo, escucha, aprende, cambia y levanta su cuerpo y su vida contra el capitalismo, el racismo, el abuso, el patriarcado. En eso consiste, siempre tejiéndose a la Pacha Mama ser «Nosotros los Indios». Hugo Blanco Galdos, legado vivo; INDIO. ¡Así Si! Prácticas y Saberes. Pueblos en Camino

Quienes tengan interés en el Legado Vivo de Hugo Blanco, comunicarse con puebloscamino@gmail.com o pueblosencamino en Facebook.

Hugo Blanco, del trotskismo a la vitalidad indígena del Perú

Hugo Blanco

Primero la perspectiva de la tradición trotskista que emana de la experiencia de la revolución obrera en Rusia, la crítica vital a su degeneración burocrática y traición. Y la sugerencia de una nueva forma de lucha defensiva armada para proteger los logros de la autonomía de la clase trabajadora .

Segundo punto, la larga e incesante resistencia de los pueblos indígenas contra la toma de sus tierras y de sus condiciones de vida por intereses coloniales y empresariales. Hoy en día, es motivo de gran preocupación si el marxismo se puede extender para acomodar las necesidades y los deseos de los pueblos indígenas que rechazan la asimilación en el modo de producción capitalista.

El trabajo de Blanco presenta un ejemplo crucial del potencial para unir estas dos posiciones y metodologías.

Nosotros los indios: Los pueblos indígenas de Perú y la lucha por la tierra, publicado por el IIRE y Merlin Press, presenta una nueva colección en inglés de los escritos de Blanco a lo largo de su larga historia de acción y aprendizaje.

El libro incluye registros de sus esfuerzos organizativos, su encarcelamiento y huelgas de hambre, y sus reflexiones sobre los valores de la comunidad indígena y las experiencias ecológicas. La obra también incluye su correspondencia con el gran novelista peruano José María Arguedas y su crítica vehemente a la posición neoliberal articulada por Mario Vargas Llosa.

Hugo Blanco, polifacético

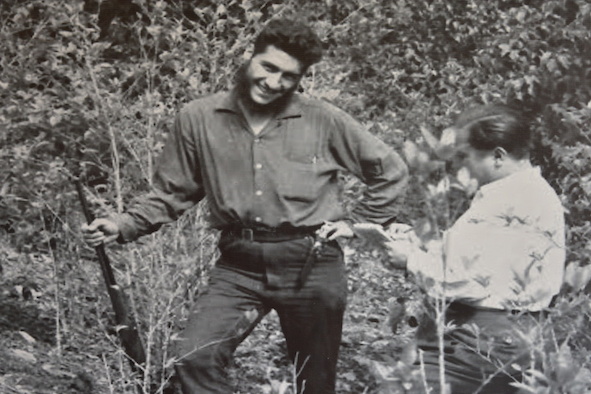

Hugo Blanco fue uno de los grandes líderes guerrilleros de la década de 1960. Sin embargo, su estrategia fue notablemente distinta de la variedad practicada en todo el continente en esa época, inspirada por la revolución cubana y las formulaciones del Che Guevara.

El propio Blanco señala que rechazó el método de grupos pequeños y móviles de soldados dedicados que pretenden enfrentar y derrocar rápidamente al estado. En cambio, Blanco pidió una lucha armada defensiva para mantener la autonomía de las áreas indígenas de los Andes, para que una revolución social democrática prolongada pudiera tener lugar en estos territorios.

En este sentido, Blanco en parte hereda ciertas ideas formuladas por León Trotsky, quien sugirió a las milicias populares como la forma socialista propiamente dicha de la organización militar.

En la década de 1960, mientras era miembro de la Cuarta Internacional, Blanco creía que este era un momento de una estrategia revolucionaria más grande que eventualmente podría superar el estado. El enfoque de Blanco también anticipa el método más tarde practicado por el Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional.

Los zapatistas también rechazaron la estrategia del foco a favor de una milicia bajo el control democrático de un proceso social indígena. Al igual que el Subcomandante Marcos, Blanco finalmente decidió que el objetivo de tomar el poder estatal no estaba en el horizonte político de la coyuntura actual.

Sería más realista y efectivo aceptar una postura defensiva que sería más o menos permanente. Esto representa una retirada significativa del enfoque anterior de Trotsky, que insistió en una inevitable confrontación con el poder del Estado y la necesidad de alinearse con los sectores de la clase trabajadora en otros territorios.

José Carlos Mariátegui desarrolló un famoso análisis del ayllu indígena, el espacio comunitario tradicional, como un área de resistencia a la acumulación y disciplina capitalista y el potencial de la acción revolucionaria socialista. Blanco prácticamente promulgó el potencial delineado por Mariátegui.

Blanco cree que el antagonismo entre el país y la ciudad es obsoleto. Esto sugiere que la solidaridad entre diferentes sectores de la clase trabajadora sigue siendo un objetivo esencial; Las comunidades campesinas indígenas no están radicalmente al margen de los procesos de capital, sino que constituyen una capa inusual de la clase trabajadora, una que es particularmente heterogénea a los valores de una sociedad capitalista.

Hugo Blanco está comprometido con la defensa de los pueblos quechua y aymara. Como Mariátegui, cree que han heredado una cosmovisión comunista que es incompatible con el individualismo explotador y la división del trabajo que caracteriza el modo de producción capitalista.

Es significativo que Blanco rechace una definición de esta población de acuerdo con la herencia genética; más bien, considera su identidad como cultural y considera que esta cultura está abierta a la participación de personas de afuera, que pueden ser transformadas y que pueden adoptar indígenas. valores.

Escribe que “gente rubia con ojos azules” puede participar en la comunidad india y que la herencia de sangre es innecesaria. El propio Blanco es de herencia mestiza; Eduardo Galeano lo describe como “ese hombre inteligente y loco que decidió ser indio, aunque no lo era, y resultó ser el más indio de todos”

Andrew Ryder

La Voz de Perú

http://lavozdeperu.com/hugo-blanco-del-trotskismo-la-vitalidad-indigena-del-peru/

Andrew Ryder discusses We the Indians:

The Indigenous Peoples of Peru and the Struggle for Land:

Hugo Blanco is a figure of great significance for contemporary thought on revolutionary potential. His ideas and practical commitment straddles two great perspectives:

First, the Trotskyist tradition that emanates from the experience of the workers’ revolution in Russia, the vital critique of its bureaucratic degeneration and betrayal, and the suggestion of a new form of armed defensive struggle in order to protect the gains of working-class autonomy. Second, the long and unceasing resistance by indigenous peoples against the seizure of their land and living conditions by colonial and entrepreneurial interests. Today, it is a matter of great concern whether Marxism can be stretched to accommodate the needs and desires of indigenous peoples who reject assimilation into the capitalist mode of production. Blanco’s work presents a crucial example of the potential to bridge these two positions and methodologies.

We the Indians: The Indigenous Peoples of Peru and the Struggle for Land, published by Resistance Books, the IIRE and Merlin Press, presents a new collection in English of Blanco’s writings across his long history of action and learning. The book includes records of his organizational efforts, his imprisonment and hunger strikes, and his reflections on indigenous community values and ecological experiences. The work also includes his correspondence with the great Peruvian novelist José María Arguedas and his vehement critique of the neoliberal position articulated by Mario Vargas Llosa.

Hugo Blanco was one of the great guerrilla leaders of the 1960s. However, his strategy was notably distinct from the variety practiced across the continent in that era, inspired by the Cuban revolution and Che Guevara’s formulations. Blanco himself points out that he rejected the method of small, mobile groups of dedicated soldiers who aim to quickly confront and overthrow the state. Instead, Blanco called for a defensive armed struggle in order to maintain the autonomy of indigenous areas of the Andes, so that a prolonged democratic social revolution could take place in these territories. In this regard, Blanco partly inherits certain ideas formulated by Leon Trotsky, who suggested popular militias as the properly socialist form of military organization. In the 1960s, while a member of the Fourth International, Blanco believed that this was one moment in a larger revolutionary strategy that could eventually overcome the state and present a prelude to a new socialist mode of production. Blanco’s approach also anticipates the method later practiced by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.

The Zapatistas also came to reject the foco strategy in favor of a militia under the democratic control of an indigenous social process. Like Subcomandante Marcos, Blanco eventually decided that the goal of seizing state power was not in the political horizon of the present conjuncture, and that it would be more realistic and effective to accept a defensive posture that would be more or less permanent. This represents a significant retreat from Trotsky’s earlier approach, which insisted on an inevitable confrontation with state power and the need to align with working-class sectors in other territories.

This presents a significant question for the articulation between Marxist and indigenous struggles. Marxist thought advocates the working class as the subject of revolutionary change. In some dogmatic formulations, this can lead to the marginalization of rural sectors and social collectives, which can be viewed as remnants of the past. However, as is well known, Marx himself defended the possibility that pre-capitalist communities could present a prefiguration of the new socialist order, and that these did not need to be dissolved into the dominant urban relations of production. José Carlos Mariátegui famously developed an analysis of the indigenous ayllu, the traditional community space, as an area of resistance to capitalist accumulation and discipline and the potential grounds for socialist revolutionary action. Blanco practically enacted the potential delineated by Mariátegui.

However, this leaves open the question of how indigenous struggles might affect the prospects of the urban mestizo working class. Blanco himself says that the antagonism between country and city is obsolete, because neoliberalism has impoverished the masses as a whole. This suggests that solidarity among different sectors of the working class remains an essential goal; indigenous campesino communities are not radically outside the processes of capital but rather constitute an unusual layer of the working class, one that is particularly heterogeneous to the values of a capitalist society. This retains, then, the broader awareness of a national and international revolutionary consciousness, rather than an acceptance of localism.

This is related, then, to the question of a definition of indigenous identity. Blanco is committed to the defense of Quechua and Aymara peoples. Like Mariátegui, he believes that they have inherited a communist worldview that is incompatible with the exploitative individualism and division of labor that characterizes the capitalist mode of production. There is, then, a partial defense of ethnic particularism; this population is uniquely vulnerable to capitalist depredation but also well-suited to resistance and to struggle. It is significant that Blanco rejects a definition of this population according to genetic inheritance – rather, he views its identity as cultural, and he views this culture as one that is open to the participation of outsiders, who can be transformed and who can adopt indigenous values. He writes that “blonde people with blue eyes” can participate in the Indian community and that blood inheritance is unnecessary. Blanco himself is of mestizo heritage; Eduardo Galeano describes him as “that smart, crazy man who decided to be an Indian, even though he was not, and turned out to be the most Indian of all.” I think that the defense of indigenous particularity, then, here presents the possibility of a broader social transformation; not merely the possibility of “respect for difference,” but a transformation of the social order as a whole, by attention to the experience and knowledge maintained and preserved by these communities.

Blanco maintains, at times, a democratic humanism. For example, he maintains that the “struggle of humanity can be summarized as the struggle for true democracy.” The ayllu, for him, presents the nucleus of a direct democracy, one that overcomes the representative alienation inherent in capitalist states. However, Blanco’s humanism should also be understood in terms of his profound respect for non-human social agents. He writes,

I beg you, for the sake of our sister the snake, of our brother the toad, of our brother the beetle, for the sake of the trees and the plants, of the butterflies, help us to survive and stop them murdering the Amazonian Rainforest.

He even speaks of the “mortal shame of belonging to the human race.” For Blanco, a socialist viewpoint is more than human; he departs from the modern European notion of human emancipation as synonymous with the domination of nature. In this regard he is quite at odds with Trotsky’s famous comments in 1924 about man improving nature according to his taste. Blanco speaks of “the strong yearning to be a jackal, viper, toad, any animal that kills only to feed, any animal that never tortures.” Blanco’s ideas on revolution can be understood as presenting the challenge to reinvent a conception of what humanity, democracy, and revolution can be according to certain epistemological insights fundamental to indigenous culture.

A Peruvian anthropologist, Marisol de la Cadena, has helped to elucidate this worldview, drawing on a decade of conversations with Mariano Turpo – a Quechua thinker who met Blanco and was inspired by his political commitment. De la Cadena develops the indigenous concept of “earth-beings,” ecological and material agents who have their own capacities, vulnerabilities, and desires. She also understands the ayllu as not only a space of democracy and collective ownership for humans, but also a place in which humans are deeply aware of their interactions with non-human elements. I think that reading Blanco together with Mariano Turpo helps us to understand how the indigenous life-world presents new political possibilities that can be dialectically integrated into the Marxist tradition.

In recent years, we have seen a series of complex efforts to integrate the revolutionary Marxist tradition with indigenous thought and practice. Among others, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Raúl Zibechi, Álvaro García Linera, Jeffery R. Webber, and Glen Sean Coulthard have made contributions to this process of incorporation. Hugo Blanco is an especially valuable figure because of his deep physical commitment and self-sacrifice, as well as the longevity of his efforts. He presents a link to Trotsky’s insights in the Russian context, to the guerrilla experience of Latin America, and toward the new spirit of indigenous struggle that has taken on new vitality in this century. His writing is fragmentary and unsystematic – because it emanates from practical struggle; but it is worth the effort to determine how our political and cultural understanding can be enriched by his discoveries.

Andrew Ryder teaches at Texas Christian University. He has written numerous articles on Marxism, decolonization struggles in Latin America, and contemporary Continental philosophy.

Fighting for indigenous and land rights in Peru

HUGO BLANCO was due to be speaking but has not received a visa in time but has sent us a short video

TERRY CONWAY, editor at Resistance Books who edited We the Indians will still be speaking

In addition we also have MARCELO RAMOS from Subverta in Brazil who will be speaking about

Brazil under Bolsonaro

– and building solidarity in Britain

Tuesday 6 November, 7.30pm

At the Community Centre, 62 Marchmont Street, London WC1N 1AB

Socialist Resistance

Noviembre 5 de 2018

http://socialistresistance.org/hugo-blanco-from-trotskyism-to-indigenous-vitality/13507