“I am passing through here … If we do not care for the territory, we will end up begging in Cali.” Cristina Bautista, sister, elder, and flight

Today (November 12), on her birthday, we would like to share more stitchings from our compañera Cristina Bautista Taquinás’s tapestry of struggle (1). In the words of her younger sister Amalfi Taquinás Bautista and her compañeras Yoly Astrid Chantre Salazar and Claribel Musicue Gasso, we will submerge ourselves in the small and impactful circumstances that marked her commitment to the territory and her communal vocation.

Every act of dignified rebellion – in its silences and words – should spark criticism and self-criticism regarding the patriarchal, colonial, statist, capitalist system that inhabits each of us. Every sadness and joy should inspire bravery to confront the contradictions from our being/doing/freeing as the women we are in reclaimed territories. Every discomfort and challenge should expose the forms of domination that we reproduce in the name of “authority” so that we can begin healing ourselves with the community. Recognizing and naming our injuries should help to heal us and not to put us in harm’s way. This is what inspires the “resistance within resistance” that Cristina Bautista Taquinás so often spoke of and what her sister and compañeras refer to when they describe her vocation and communitarian trajectory, her successes in spite of adversities, and the pending challenges that endure so that we – as women – can continue in movement.

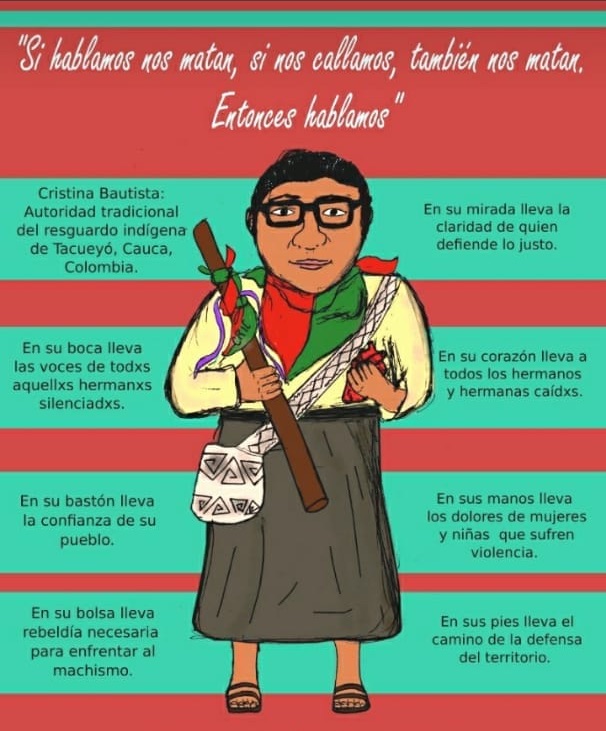

Cristina Bautista Taquinás, a woman with an uncontainable spiritual force, opened a path for us to free ourselves of machismo and authoritarianism. She sacrificed her life – along with Asdrúbal Cayapu, Eliodoro Finscué, José Gerrardo Soto and James Wilfredo Soto – to defend and care for the territory. She left a legacy that will only be forgotten if we rashly accept the power relations that oppress us. In the name of “gender inclusion,” these oppressive power relations only allow us to speak in the spaces permitted by all of the systems of domination.

We invite you all to be moved by Cristina’s struggles, which undoubtedly include other resistances and rebellions that are currently emerging in other parts of this “world of worlds.” We invite you to allow your memory, journey, and spirit to be immersed so that we – as women, youth, and guardians of the territory in community – can forever do right by Cristina. This should make us smile as we encounter one another and weave ourselves together in struggle…living as a people that we can and must be(come).

I. Testimony of Amalfi Bautista Taquinás, Indigenous Resguardo (Reservation) of Tacueyó

Sweet Words:

She liked to do everything. She was not fussy. She loved reading, and she had many books. She left us many books to read. What she most shared with us was her smile, her joy, her desire to live, to breathe, to struggle. She had many dreams and always thought in terms of the big picture. She said if someone had a dream, they had to think big, even if it had a price. She was always smiling and looked for the good, even in the bad. I never saw her angry. If she saw you angry, she would find a way to make you laugh in order to make you forget. She had a unique character. She looked for solutions to everything, and we never saw her angry.

She had to take on a strong character in her work in order to instill respect in the people who disrespected her authority. The decisions that were made collectively had to be fulfilled. Even in spite of the strong character that she had to assume, we never saw her angry or in a bad mood.

She always had a good relationship with her neighbors, friends, and family. She was always an example, and she left us many teachings. She was always there to give us advice, speak with us, hug us. She was very loving. She was a person who left many gaps in our lives. You cannot find the words to describe how she was as a sister. She was unique. She always asked us how we were doing: “Hi sister. Why are you sad? Why are you happy?” She was like that.

Bitterness that endures

She had many difficulties because there were several compañeros who did not allow her to work with the community the way she wanted to, but we did not speak much about her work (2). She lived with a lot of stress. She would arrive sad and crying, but she said that she could not tell us about what was going on. So, when she got home, we tried not to ask her about her work. Instead, we would try to help her destress by making her laugh. She had many problems and difficulties in her position even though she did her work well.

What bothered her about the organization was the hypocrisy. She said that there were many people who would publicly say one thing and in private say another. There were people that would pull in one direction and then the other. She put a lot of effort into the work, but there were always hypocritical people and that affected her. You would see her crying or sometimes pensive because of the difficulties in her community. She said that her community lacked a lot of consciousness about the crops used for illicit purposes because the majority of the problems in the territories were due to those crops (3).

Here in our village, she tried to raise consciousness, but – at times – they treated her badly. One time, they asked her: “Why was she getting involved in this if she didn’t know anything about it? Wouldn’t it be better if she shut up and gave up that stick (palo)?” That’s what they told her in one meeting when she carried her chonta (wooden cane that endows authority) (4). That was painful because the community was not conscious, and she was providing guidance with a lot of love. But she was treated badly when she spoke about that issue.

To this day, it pains me because she gave her life, and the majority of the problems that remain with us are caused by those crops used for illicit purposes. Even so, the community does not gain consciousness and continues planting the crops as if nothing were happening. You ask yourself: How many more deaths are needed for the community to gain consciousness about those crops? This is not something that can be covered up or hidden. You want people to think in a different way and understand that you can get ahead in a different way, but sometimes it’s almost impossible to tell the community that there are other ways out when they don’t want to see it that way.

Dreams on the Way (5)

Defending the territory was one of her dreams, but sometimes I didn’t understand. I would say to her: “Cristina, why do you struggle? Get out of there. You are risking your life.” She would tell me: “Before you know it, they will kick us out of this territory, and we will have to go live on the streets of Cali or Santander begging for charity. That’s why we have to struggle for our territory.” She was very clear about this—the struggle for the territory. She wanted the community to get ahead. She said that the “illicit crops” could be changed, that it could be done, and that we had to struggle for a community.

She loved to travel. She said that she could never see herself in a home or having children. For her, life was travelling. She visited many parts of Colombia, and she enjoyed the adventure. She would travel by motorcycle for weeks. One time, she took my parents to Santa Marta, Barranquilla, and Cartagena, and they got to know several cities. She said that that was her life. She also struggled for mistreated women. She dreamed of getting her nephew and niece ahead. She said that she would get them to the university even though their father was not there (he died in an accident).

She also wanted to create a tailoring business, thinking of the women who are victims of the conflict. We had two professors teaching us how to tailor clothing for women. She named the business Kiwe Ate and took into account the women who were heads of households, as well as her sisters. We started building it, but we did not finish. It’s there, but I don’t feel capable of moving that dream forward. When I use that machine, I begin to cry. I am reminded of her and how she counseled me. She told me that I always had to struggle when I was at those machines.

It’s difficult now because she’s not here. She gave us strength to struggle, to dream. It’s unjust that the good people go. Like one of my cousins said: “The good ones go. The good ones don’t last. I prefer to be bad.” Cristina was so good. Why did she have to go? Sometimes I don’t understand the mysteries of life. For me, she hasn’t left. Sometimes I sit outside the house waiting for her to arrive.

Feminine Stitchings

She wove herself into the fabric of the women in the territory through her thesis on the armed conflict that left families in pain. She wrote her thesis about the armed conflict that left families in pain. She visited many families, many women. She said that through these experiences she came to understand that women suffered so much from machismo, from mistreatment. She dreamed of a better future for women, so that we would not have to just depend on men because we – as women – also know how to work, defend ourselves, and have our own resources. She dreamed of preparing women to study, to learn about music… So that they would not have to stay there.

Many of the women were the heads of their households. Sometimes it was very difficult to work in the countryside, and they had to find other ways to get resources. Cristina dreamed of a change for women. Since she left, the dressmaking group in our town has not gotten back together. I feel powerless. I ask myself what I’m doing. It was my sister’s dream, but sometimes I feel like I am uncapable of moving it forward. She dreamed of the best for women. She said that we should not allow ourselves to be mistreated or beaten. She said that we were born to do great things. Why couldn’t a woman become president or governor? She always opened spaces. She said that women could be there because they had the same abilities or even more. That’s how she connected with the women.

She met many women and became known. The Nasa Women Weaving Thought (Mujer Nasa Hilando Pensamiento) movement nominated her to represent the community during an assembly. They chose her in the gymnasium, but she was not even at the assembly that day. Then there was another meeting, and they asked if she wanted to participate as a candidate for the Newesx (the Nasa authority). She said: “If it is God’s will, I will.” My mother told her: “Cristina, it is your decision. We will support what you decide.” At that time, they called her from Spain to offer her a position with the United Nations that would pay very well. She told my mother about it and decided: “If it is God’s will, I will serve the community because they elected me. If not, well, they didn’t elect me.”

Collective Doings

There were many people on the day of the election. A lot of people voted. She was elected along with others that would become the authorities of the Tacueyó Resguardo (Reservation) in Toribío, Cauca. That afternoon, she arrived and told me: “Oh, sister (hermanita), I was elected.” I felt such joy. But who could have guessed that such joy could be transformed into our worst days? If she had never gone to that gymnasium… If she had never accepted… Surely, she would still be here with us. Who could have imagined what would happen? That is how she became an authority.

Her commitment to the Indigenous Guard (Guardia Indígena) was constant (6). She was very concerned about them because they were the ones that took care of the territory day and night. Sometimes they did not even have food. That’s why she wanted the indigenous guards to have the appropriate conditions and opportunities for their families. She was very close with the people that cared for the territory, and she accompanied them whenever she could. Even the night before the massacre that took her life and the lives of four indigenous guards, she accompanied the guard post although it was not her turn. She – as an authority – was concerned with the risks because of the threats. She did not doubt that she would remain vigilant until dawn, as the guard always does.

One time, some youth called me from the Thé Wala foundation in Popayán. They told me that Cristina had taken them there so that they could get off drugs and be rehabilitated. Some of them said: “We received death threats, but no one had looked us and said: ‘we’re going to do something with you (the youth).’” She chose 24 of the most advanced youth and brought them to the foundation. Others said: ‘We finished high school, and we have a technical degree thanks to Cristina. Even though we were the bad ones in the community, she believed in us and gave us an opportunity because we could change. She came and sat with us in the foundation and talked to us about many things.”

Even though she was in that position for very little time, I meet people who tell me that she helped them with this or that. Even though it was a short amount of time, she touched the lives of many people. She arrived in the position seeing the bad in the community (such as the mistreated women and the youth consuming drugs) in order to change it. It’s shocking to hear everything my sister did in such a short amount of time.

II. Testimony of Yoly Astrid Chantre Salazar, Indigenous Resguardo (Reservation) of Tacueyó.

Return to the Territory

She left the resguardo (reservation) when she was a girl to work and support her family. She looked for opportunities to study until she succeeded in graduating from the Universidad del Valle as a Social Worker. When she returned to the territory, she was very excited to listen to and experience all the beautiful things they said in the academy about the organization (7). From the outside, she heard how lovely and organized our struggle was, but – when she arrived – she found high levels of machismo, inequality, lack of opportunities for youth, drug addiction, armed conflict, recruitment of minors, single mothers, couples getting together at a young age … She said that these problems should be discussed beginning in school and that there should be a curriculum that talks about gender, made by and for women.

She initially arrived in 2016 to work with the Victims Unit of the Mayoral Office of Toribío, and she learned about all of these forms of violence there. She concernedly encouraged women not to stay quiet—but to opine and speak. Really, she started a whole process of raising consciousness among women. In 2017, she believed that they would rehire her in the Mayoral Office to continue this project. She even submitted a project proposal, but it did not work out that way, even though they did not pay for all of her expenses during her trips and they owed her money. She linked up with women and reactivated the women by motivating them and walking alongside them. Despite not having money, she did not abandon the process with the women and worked closely with us to convene us and bring us together as a movement despite all the adversities.

The Women’s Movement

Our struggle goes back to the Cacica Gaitana, but it was not consolidated due to the lack of support and the opportunities denied to us by our own leaders as a consequence of the historic patriarchy that exists (8). Women have wanted to get organized many times, but they always confront the same finger-pointing that we do today. And that is why they desisted. The women’s process would be born and then fell apart again. However, when Cristina arrived, we got together with some women – many of whom were young – and had some new ideas. Cristina shared the idea of reactivating the process. All of us decided that it would be named the Women’s Movement (Movimiento de la Mujer) because – if we wanted to strengthen our roots – we needed to reclaim the historic name that our elders gave the process. We also did this because the first women’s organization in Cauca was also born in Toribío, and it expanded to a region-wide process. So, in memory of our elders, we used the name Weaving Thought (Hilando Pensamiendo) because in the fabric of life (tejido de la vida) we all need to bring together every stitch until we find the true unity amongst women at the local, zonal, regional, national, and international level. For us, it was a strategy because we had analyzed that the women were very divided, and we were losing our sensitivity to the pain of many women.

Cristina dreamed big. Her dreams flew far into a future of equilibrium and harmony with equality of opportunities for women. She dreamed of an action plan where the most important thing was reaching the women in every town through different strategies because the movement did not seem to matter much to many women, due in large part to the way the movement was stigmatized. Many people saw us as divisive, and many times we heard leaders call us “subversives.” But Cristina just smiled. To be concrete, we reactivated the movement when Cristina arrived. She was very concerned because Toribío had the second highest rate of sexual violence in the country in 2016. Additionally, women had participated in the movement before, but it was not autonomous participation because they spoke the same language as the leaders. I met many women who said “we are present,” but they repeated the same machista discourse. We analyzed this a lot, and Cristina invited the women not to be quiet any longer.

I remember one unpleasant experience from my work at that time. I was in my office and not doing well psychologically. I was in bad health, and – in addition to that – they had asked for my resignation letter even though they knew about my pending health issue. But that was not the hardest part. The hardest part was the humiliation and devaluation of my work. That’s when she arrived and asked me what was going on. I could not keep it together and cried because I felt like I was suffocating. She told me: “Let’s go because the women are meeting at Doña Carmelina’s place. Tell the women to see if that makes them truly understand the situation of women.” I went with her, and I could vent there and get it off my chest. She talked about the issues related to these problems more broadly. She was always concerned because she had seen a lot of pain in her travels. Because machismo is still very strong in the communities and many women remain silent. She longed to get to know the autonomous territories of the Zapatistas. That was another one of her dreams because she had read a lot about them and their struggles. “They have achieved so much. We must unite with them because they (ellas) achieved so much together.” It also meant that our women’s movement needed to be recognized around the world because it was born in Toribío, and Toribío is the birthplace of women’s resistance.

Those who do not have a price do not sell out

We had many needs. We lacked our own space. We met in the park, on the corner outside of shops, and in some homes. Sometimes we met without lunch. She told me that an armed group – perhaps the same one that silenced her – had approached her and told her: “If you need money, let us know so that we can help you fulfill all your dreams.” We reflected on this and decided that we should remain conscious because you do not negotiate consciousness with anyone or anything.

She walked around the territory without complaining or getting tired. Many times I saw her wet and hungry walking from Toribío to Tacueyó. She traversed the entire municipality. She always said: “Never tire of struggling,” as if she knew that she would not be with us for much time. “If someday I get off this train at some station, you all need to continue the journey. I don’t know, but I won’t be here for long. I am only here for a short while.” In one of our conversations, she said “I want to become a senator, representative or ambassador,” thinking big things could be done from there. As she walked through the territory, she grew increasingly sad seeing how people became more degraded by the so-called illicit crops and the consequences that they bring to their families.

We spoke for the last time on October 28, one day before the massacre. I went to see her after she called, and she was on her way out with her baton when I arrived. She told me: “I am going to see what is going on with that truck that has been down there for over an hour.” I took her by the arm and told her not to go. I told her to call the Indigenous Guard to see what was going on. She responded: “From now on, I am not going to expose the Indigenous Guard any longer. I don’t want any more guards dying. If I have to give my life, I will do it. I already spoke with God about it. Not one more guard will be murdered.” I knew of her sadness and impulsiveness, so I was able to stop her by talking about women’s issues, and I did not let her leave. She told me about how difficult the situation was: “I don’t know how this is going to end, but we have to be prepared. We have to support the Indigenous Guard more because they are sticking their necks out to defend life and the territory. And it pains me because they put up with hunger and do not get paid. Many sacrifice their families for the community, but the ones that threaten and murder them are the very commoners (comuneros) that they care for.” (9)

Threats and Premonitions

She was very concerned about the situation and told me that she needed a ride urgently because she had become ashamed of bothering people so much about getting rides here and there. I offered to take her on my motorcycle when I got freed up, but she refused in order to keep me from being exposed: “There are things that I have not said, and I prefer to be quiet. It’s delicate for you to be seen talking with us because something could happen to you. They even threatened the motorcycle-taxi drivers and prohibited them from taking us places.” That day we made an offer to get a motorcycle for her on credit. She also recommended that I continue the struggle and strengthen the Women’s Movement. “Despite the situations that might happen, we cannot give up. I know that you and Claribel make a good team. As a youth and an elder, you can make things happen. I trust in you.”

I told her that we still lacked many things in the movement, that she could not leave us alone, because she seemed distant after becoming an authority. She responded: “It’s not easy, but I keep you in mind even if I am not with you. I have even talked with the other authorities and asked about getting some resources for the work with women in Tacueyó because they do in Toribío and San Francisco. But it is difficult. I am not here for long. I did not come to stay. I am fulfilling God’s plan for me, but, wherever I go, I will always be with you. Sometimes, I think that by going far away I can help you more. When I finish the mandate that was delegated to me by the community, I will be able to do many things for the women and then I will see the light of women shine.” She wanted to meet with the women. She had planned on it various times, but they did not arrive. She had a lot to recommend, but the will to understand her work was lacking.

She had a lot to share. If I had known that would be our last conversation, I would have stayed up all night with her listening because we had not been able to talk since she had become an authority. “The only thing that I will tell you, Yoly, is that if the community does not reflect on what we are living through after everything that has happened, then I don’t know what is going to happen with the community. I don’t know what they are thinking. They should think about their children and their families. My mother and my brother tell me to turn in the cane. They tell me that I shouldn’t carry those things because they are threatening anyone carrying all that. But I asked them: ‘Why? Is it as if I’m carrying a weapon? Is it as if this cane is going to harm people?’ I know that my mother suffers, but I have told her that they need to be prepared.” She told me that three nights beforehand she had a vision while she was sleeping. She saw three armed men dressed in black outside of her home. She was so alert that she called the pastor and told him about her fear. The pastor called brother Edwar, who lives close by, to check it out. The commoner (comunero) confirmed that he saw three armed men dressed in black around her house. At that moment, they got up to pray. She told me: “I am not scared of dying. For me, death is a victory—I feel for the living. I do not have children, and God has the word. The only thing I have and think about is my mother.”

Around 9:30 on October 28, she felt something on her right shoulder, and I told her it was a bad sign. She told me that she felt something that caused pain in her head and showed me. “It feels as if they were going to take my head off. I feel like it’s empty.” I asked her to take care of herself, not to travel alone, not to expose herself, because, in the end, people would not even be thankful. “I take care of myself, but God has the last word. Everything is written. The only thing I will say is that this community needs God.” She also told me that the National Protection Unit (UNP) had offered her a bulletproof car for her protection, but that she was clear that she had arrived as an authority and not to travel around in a car like that. I told her to accept it because we have to beg for rides in the movement and it is necessary. “That’s not for me. It is not part of my principles.”

Perseverance and Dignity

When she left for the Nasa Constituent Assembly in Toribío, she asked for four spaces for women, but the authorities denied her request. However, she was so on top of it that she invited us to participate when she found out that it was about to begin. “They did not give us a spot, but we will participate even if it is from the outside.” We went, and that’s how we did it. When we arrived at the tulpa, she reminded them about the spaces reserved for the women’s movement and asked if it was possible or not. I remember so clearly that a woman leader at the tulpa (10) told us: “There are 30 spots. Those of us that are here were supported by the cabildo and it is all full. If you want, you can stay as observers, but not as part of the 30 spots that were already established. That is to say, you have to pay for your own expenses.” I felt the most humiliated, looked at Cris, and said: “Let’s go!!!” Four of us from the movement were there, and Cris said: “Even if it’s from the outside I’m staying because I came to learn. It’s not a problem for me. I brought my food, and that’s that.” The truth is that I did not return, and I thought that she didn’t either.

Six months later, she told me that the 30 delegates were discussing the profiles for nominating authorities (Kwekwe). They had talked a lot and concluded that none of them were qualified. So, Fredy Cuchillo said: “None of us here have the profile or meet the requirements. That’s enough. The only person that qualifies is Cristina, so pass her the microphone.” That’s how they did it, and, since it was already mid-day, they asked her: “Now what do we do?” She jokingly responded: “We go to lunch.” Since that day – six months after listening in silence as an observer without a voice or a vote – she has been a spokesperson. They started to treat her better by then because she had become friends with some of the leaders, and they even went to her house to pick her up to take her to the tulpa. She said that they questioned her religion a lot in that tulpa and that she remained quiet for a long time until she asked them: “Why do you all talk so much? Do we tell men to leave their women and find another? Do we tell people to grow marijuana? Let’s focus on supporting the organization and getting it in order.”

Little by little they included her until she ended up in the Constituent Assembly group. That was a struggle, and her name started to appear as a candidate to become an authority since she made it to that position and because she was committed to learning more about the indigenous process and from the knowledge of the elders. When she told me that her name came up to be nominated as a potential authority, I got very happy and said: ‘Yes. You are the one we need.’ She said: “That is not my plan. I am only here temporarily. I am applying to study abroad and it should be ready soon.” But her name kept coming up in the villages. Then they had to travel around the territory in groups to share the results from the constituent assembly process. She called me over at one of the meetings to tell me that one of the group members had only allotted her one minute to share a greeting and that he was already campaigning for another candidate. I told her: ‘Take the time you need because that’s the way things are done here.’ She responded: “Yes. That’s what I’m learning.” After a while, I asked her what she was going to do because the situation was very difficult, and I thought it was better for her not to accept the candidacy to become an authority. She responded: “I already decided. I fasted for 7 days so that God would let me know, and he gave me this mission.” I never spoke to her again about it.

On the day of the election, many people voted, and they elected her. I hugged her and congratulated her on the day that she won. She told me she got scared when she saw that the entire community raised their hands after she was named. Many of us from the Women’s Movement accompanied her, and I personally offered her all of my support because she began to suffer from abuses of power on behalf of other authorities. It was very difficult at the beginning. She was stigmatized because she came from the Momen’s Movement. I even heard a leader say: “Now that the skirt is a neehwesx (authority), the Women’s Movement is done.” That’s what they wanted, but the struggle continued. I have wanted to abandon the process many times, but I remember her recommendations and petitions to continue supporting the women. When I feel frustrated, I hear her words. When I cannot see a way out, she appears to me in dreams. One night, I dreamed that she was showing me a beautiful apple orchard with very healthy fruit, and she said: “That’s how the Women’s Movement will be.”

III. Testimony of Claribel Músicue Casso, Indigenous Resguardo (Reservation) of San Francisco

What remains of her

The thing that I remember the most about Cristina is her smile, even though she was confronting many difficulties. I never saw her get angry or stressed with any of us. It might have been her aroma or her energy. I don’t know. I remember that she distanced herself quite a bit when she became an authority, but when she came by you felt a lot of tranquility. Even though she was not the coordinator, she always generated a lot of energy. Beautiful energy. I remember her persistence and the effort she put into it. Perhaps her greatest contribution that has not yet been applied is learning to build amongst differences.

What is missing

Comprehending and understanding the system. I think, as peoples, we have always been resisting the system, but we have not been able to name it: the capitalist system. It is fundamental for women and men in the territory to be conscious of it so that they can contribute to the struggle – not just of the Women’s Movement – but of the organizational process. We know that there are many ways of seeing it, that each of us is a different world, but these thoughts must encounter one another in this struggle for transformation.

We still do not have a document that consolidates the movement and says what we’re building and how we are going to struggle. There are many ideas, but we should have one discourse. It should not be copied, but it should be in support of a shared vision of struggle. The movement is lacking women that are professionals who are conscious of the women’s struggle. One of the problems is administrative. Our elders (mayoras) did not move forward because their struggle wasn’t written down. There was no written document. So, there are many elders (mayoras) that have it all in their heads, but it is important to learn how to write.

What we should heal

I have some very ugly memories from when we had not yet transitioned to self-government and there were still governors. But now it seems the same to me, as if the only thing that changed was the name. But that is only my perspective. I remember that there was a man that acted very badly with all of the women from the movement. It wasn’t just against Cristina, but she was targeted the most because of her position. She spoke of the women, and that’s why she would be more attacked than the others

We were still more submissive. We still weren’t as advanced in the leadership. There wasn’t even a relationship with the authorities. I don’t know what to call it. But they would watch us and watch us, and they would always ignore us, distance themselves from us, and make fun of us. In fact, when they murdered her, that same man said: “Now the Women’s Movement is going to be finished because that skirt died.”

That man’s words are hurtful. I don’t know if it is personal or if it is because we are part of the women’s struggle. I feel that it is because of our movement as women. I, for instance, have known that man for a long time, and my relationship with him was fine. We would greet each other and everything before he became an authority. But, when we started the women’s process, he treated us differently. The authorities treated Cristina harshly. I don’t mean all of them, but the majority. The women in those positions were very aggressive, and they took us out of those spaces many times.

I remember, for example, that they did not give us an office in San Francisco, but there was a young man that was very generous. He gave us an empty office that was only used on Saturdays. So, I got comfortable in that office along with another elder (mayora). We called Cristina and all of the women, and they arrived. We told them that we had finally won a space and that they had finally given us an office for the women.

They went to get to know the space. We installed a computer and all of that, but two women arrived and kicked us out of there. It wasn’t even the young man. It was the two women. They shut the door, and they did not even want to let us take our computer. ‘Get out of here! Get out of here!’ As if we were not part of the structure, right? We’ve lived through a lot of things like that, which have not even been told. But they were always very hard on Cristina. They were always making fun of her, looking at her the wrong way. I don’t know what was going on with those authorities, but I felt it was like that. She always positioned herself, and she didn’t care if they made fun of her. What mattered to her was continuing and doing community work.

A disputed path

As women, we don’t really talk about autonomy, but we have been doing work. One of these projects is the women’s circles or tulpas. There are many forms of autonomy, but we think that this is one of the spaces where women can come and talk about forms of caring (los cuidados), about the values of Nasa women. From the women’s movement, we have affirmed that one of the pillars of struggle is autonomy.

We have talked a lot about how to generate autonomy within the organization. We have seen that is very complicated due to all of these situations, but we have been able to do it in Toribío even though women from other resguardos (reservations) may not be able to arrive due to the long distances. We have been in this process for more than three years, and we can see how we’re growing. More than 80 women now participate: talking, meeting, conversing about Nasa values, and also making a Tull (garden). We also made a tulpa and planted medicinal plants around it. We talk a lot, but we also do. I don’t know if they feel like this is autonomy, but that’s where we’re at. And it is a very beautiful process.

Pending Challenges

Unfortunately, the ambition for more resources continues to grow stronger here. You see a lot of money here in Toribío. I remember that someone – it might have been Father Antonio Bonanomi – said “What will happen to the Indians when they get money?” For example, in the Life Plan (Plan de Vida), the organization started asking for resources without input from the community. They started writing up reports for outside organizations, but they weren’t with the community. The worst is that this strongly affects the women because the projects are supposed to have a gender focus. So, they get resources in name of the women, but little changes in the lives of women.

Cristina left two project proposals written out, but we did not become a legal entity because we wanted to remain autonomous. The Nasa Project (Proyecto Nasa) gave us a document, but anything for the Women’s Movement has to go through them. They want to administer and implement the projects, but with very little input from us. It’s painful that our women’s process and everything that Cristina left ends up benefitting just a few people and that it does not achieve the impact in the community that we hoped for. Women have wanted to get organized many times, but they are unable to do so with full autonomy because they are under certain regulations. You can’t do it that way either.

After what happened to Cristina, many projects have arrived, but the women are still under the same conditions. If we speak up, they tell us that we are self-interested and that we’re there for the money. In the end, many things are done in the name of women, but they don’t reach the women. Instead, it is dividing the women’s process. It seems that they do not want to strengthen our process. The compañeras that dare to speak up or denounce these things are distanced from the organization or stigmatized as contrarians. This makes many things difficult because the same thing happened to Cristina. Fortunately, the community trusted her, and that’s why she became an authority. This was very important because the community elected her, not just the same ones as always.

November 12, 2021

Text written by Vilma Rocío Almendra Quiguanás

From the Mother of the Forests (Kauka) in a territory called Colombia

Peoples in Movement

Translated by Anthony Dest. Many thanks to Mathilda Shepard for her feedback on the translation.

(1) Compañera means friend, comrade, and buddy in Spanish.

(2) The original version attends to the gendered aspects of the Spanish language. When speaking of groups that include various genders, the author used “x.” When speaking of groups of only men or women, the author used “o” or “a” respectively. The translation reflects the original version’s specificity. In this case, “compañeros” refers explicitly to men.

(3) “Crops used for illicit purposes” refers to plants deemed illegal by the Colombian government, such as marijuana, coca, and poppy. The speakers refer to them in this manner to stress that the plants, as such, do not carry the stigma associated with illegality. In fact, many of these plants possess spiritual and medicinal properties.

(4) Nasa authorities carry a wooden cane that demonstrates their position in the community.

(5) The original Spanish title for this section – Sueños en camino – suggests multiple uses for the term “camino,” which could also be defined as a path or a journey.

(6) The Indigenous Guard is an autonomous self-defense group that protects indigenous communities.

(7) The “organization” refers to the indigenous movement in Cauca and particularly the Proyecto Nasa in Toribío, Cauca.

(8) Cacica Gaitana was an indigenous woman that led a movement to confront Spanish colonialism in the 16th century.

(9) Indigenous peasants in northern Cauca are often referred to as “comuneros,” or commoners.

(10) The tulpa is a sacred meeting space for the Nasa. It consists of a fire built around stones under an open-air, circular edifice.