«Bautizo de Sangre»: Colombia, hacia un campo de concentración a cielo abierto

Robin Llewellyn es un hermano. Recorre territorios y afectos, recogiendo para contar. Cuenta con detalles, con datos, con cuidado, para que quienes no saben no puedan decir luego «nosotrxs no sabíamos» como es costumbre en la indiferencia cómplice y en la complicidad enmascarada de indiferencia. Por ahí anda sólo, pero acompañando y acompañado, muy acompañado de afectos en su recorrido por los territorios de la vida negada y olvidada y del terror contra la resistencia y la dignidad. Robin anda por Colombia y ahora dice que la Nueva Colombia está siendo Bautizada en Sangre, en un artículo suyo en inglés que publica Intercontinental Cry y que compartimos de inmediato.

Hay un plan de ocupación integral total del territorio en Colombia. Una agenda de largo tiempo que se cumple. Un experimento fascista del nuevo capitalismo. Durante los gobiernos de Uribe esto avanzó mucho y se llamó confinamiento. Ahora, aún antes de que Uribe entre a gobernar desde la supra-Presidencia permanente y transnacional que le asigna la mafiosidad del nuevo orden de terror-fascismo-mafioso, ya empezaron a someter. Ahora mismo el ejército ocupa una escuela en territorio indígena suspendiendo clases. Es lo mismo que hicieron en Cherán, Michoacán, México, los «caballeros Templarios» en coordinación con gobiernos, partidos, fuerza pública y todo el régimen, antes de que las mujeres se levantaran ese día de abril hace 6 años para echarlos junto con el gobierno, la policía y los partidos políticos (algún día, ya tarde, ojalá siguiendo su ejemplo lo hagamos acá…es eso o la esclavitud y la muerte). Pueblos, barrios y ciudades enteras, controladas y ocupadas por militares, policías y paramilitares junto con narcos y delincuentes (se cambian uniformes entre sí). En Puerto Torres, al sur del Caquetá, una escuadra paramilitar entró acompañada del ejército. Ocupó la escuela, la casa de la parroquia, sometió y masacró según el entrenamiento recibido en la «escuela política» del Bloque Central Bolívar. Silencio y terror. El comandante, rubio, arrogante, aterrador, salía al parque rodeado de escoltas a asolearse. No se le podía mirar o se llevaba al interlocutor. Sin comida, a golpes, deshidratados, colgados de árboles a diario, atados de los pies, tenían que observar en su agonía cómo cortaban en pedazos con motosierras, a quienes bajaban de los árboles, uno tras otro. Tenían una técnica establecida para enterrar los cuerpos reducidos a lo que cabe en una bolsa de basura. Les abrían el abdomen y el tórax para que en su descomposición no se llenaran de aire estallando de modo que pudieran ser ubicados. Hasta los cadáveres desaparecieron por miles. Todos menos un poco más de una decena que el ejército permitió sacar, seguramente para transmitir su mensaje de terror. Mataron mujeres luego de violarlas y usarlas. Mataron guerrilleros, auxiliares de guerrilleros, según dicen, pero la gente cuenta que no, que mataban por matar, que era una escuela de la muerte. Tres años en un territorio militarizado cerca de las bases militares más sofisticadas de los EEUU sin que apareciera el ejército o la policía. Tres años de un campo de exterminio y según se oculta pero se sabe, hubo más de un centenar en todo el país. Fue el Estado, con el Pentágono. Escuelas de la muerte. Campos de exterminio. Bautismo de sangre, silencio y terror. El mono y otros de los comandantes están libres y actuando. Toda esta formación y esta escuela, las tropas asesinas, las técnicas…todo esto está listo para llegar a donde quiera que los vayan ubicando. Entre las víctimas reclutarán a los asesinos. Si no matan, ya saben cómo morirán. Esta máquina de terror para la acumulación, le da el petróleo, la selva, la riqueza a transnacionales, elimina «excedentes» de población, activa la economía y se hace a mercado y recursos escasos. Países enteros…Colombia, escuelas de la muerte para la ganancia. Quienes escaparon tuvieron que callar. Quienes fueron ubicados al escapar regresaron a morir, a manos de la fuerza pública que los devolvió a Puerto Torres.

Confinamiento: Controlan lo que entra y sale. Cómo se viste la gente (especialmente las mujeres), los horarios a los que se puede salir a la calle. Las entradas y salidas de las localidades que se autorizan o niegan según los armados. Lo que pueden llevar o traer, aún de comida, manteniendo a la gente bajo hambre, temor y disciplina. Colombia: Un campo de concentración a cielo abierto. Allí entran las transnacionales a apropiarse de trabajo esclavo, riquezas, recursos y todo lo demás. Y claro…terror. Torturan, desaparecen, matan, violan con técnicas de tortura y masacre para las que han sido entrenados.

Con ello logran que todo un país se convierta en una hacienda de transnacionales y los fascistas como Álvaro Uribe y su máscara Duque, garantizan el «control territorial», es decir, la consolidación de este modelo en todo el país. Ni la conquista, ni la esclavitud, ni la inequidad, ni el abuso son cosas del pasado: NUNCA COMO AHORA Y PRÓXIMAMENTE HA SIDO TAN DESIGUAL, AUTORITARIO, MACABRO EL MUNDO AL SERVICIO DE ASESINOS CODICIOSOS INSACIABLES. Apenas comienza la consolidación a nivel nacional de este plan, acompañada de guerra contra Venezuela y la extensión de este modelo de fascismo y confinamiento a todo el continente. RESISTIR O ESCLAVITUD Y MUERTE! Este país está siendo bautizado en sangre. Quienes en Colombia aún no lo reconocen ni lo creen, ojalá despierten y nos organicemos. Quienes fuera creen que este es un asunto de Colombianxs, se equivocan, es un experimento que ya anda por México y más allá…es el mundo por-venir. Es la nueva fase del capitalismo a la que retorna, más cruel y sin miramientos de raza, pero patriarcal, machista, racista y clasista, una esclavitud y un desprecio por la vida como jamás hasta hoy se ha vivido y sufrido, para que unos pocos, cada vez menos, se enriquezcan poseyendo entre sí todo el planeta y toda la vida. ¿Dónde Estamos? En tiempo real. Pueblos en Camino.

A new Colombia is being christened in blood

At ten o’clock last Wednesday night (July 4, 2018) a group of masked assassins entered the house of Darío Dovigama (30), a leader of the Embera indigenous reservation of Cañabravita in southern Colombia. Dovigama was shot and killed without hearing a single word.

His father, Francisco Dovigama (59) grabbed a hunting rifle and fired back. He was also gunned downed.

Dario’s wife pushed their children out of a window to safety before raising a machete against the attackers, who, having run out of bullets, dragged her out to the patio by her hair and tried to kill her with the butts of their guns. Her screams alerted the neighbours which caused the assassins to flee on three motorbikes.

The local indigenous community was about to hold a consultation on the issue of oil exploration in the area. Prior to the attack, community members reported a proliferation of threats delivered by pamphlets.

On Saturday, (July 7), armed men visited the house of Dilson Borja (29) in Colombia’s second city Medellin, and gave him 24 hours to leave the city or be killed. Borja is an indigenous guard also of the Embera Peoples, but from the northern region of Uraba from which he had previously been displaced.

In the past, Borja has campaigned on the restitution of land that was illegally seized during the civil war. He has also opposed mining, and supported the unsuccessful presidential bid of the leftist Gustavo Petro.

The night before (July 6), in the north-eastern region of La Guajira, two armed men arrived by motorbike to the house of the Wayuu activist, Yelenka Gutierrez. They tried to force their way in, but they were kept out by her brother-in-law, who was shot twice.

Gutierrez, a former Secretary of Indigenous Affairs for La Guajira, has been threatened in pamphlets by a group calling itself the Equipo Contrainsurgencia de la Alta Guajira (Counter-insurgency team of Upper Guajira). Other members of the Wayuu human rights NGO Nacion Wayuu have also previously been given 24 hours to leave the region. The Guajira was largely spared by the country’s civil war, and Nacion Wayuu chiefly campaigns on issues related to the social and environmental impacts of the region’s Cerrejón coal mine, the largest open coal mine in Latin America, and on alleged corruption and mismanagement by the state’s body for addressing childhood malnutrition in the Guajira, the ICBF.

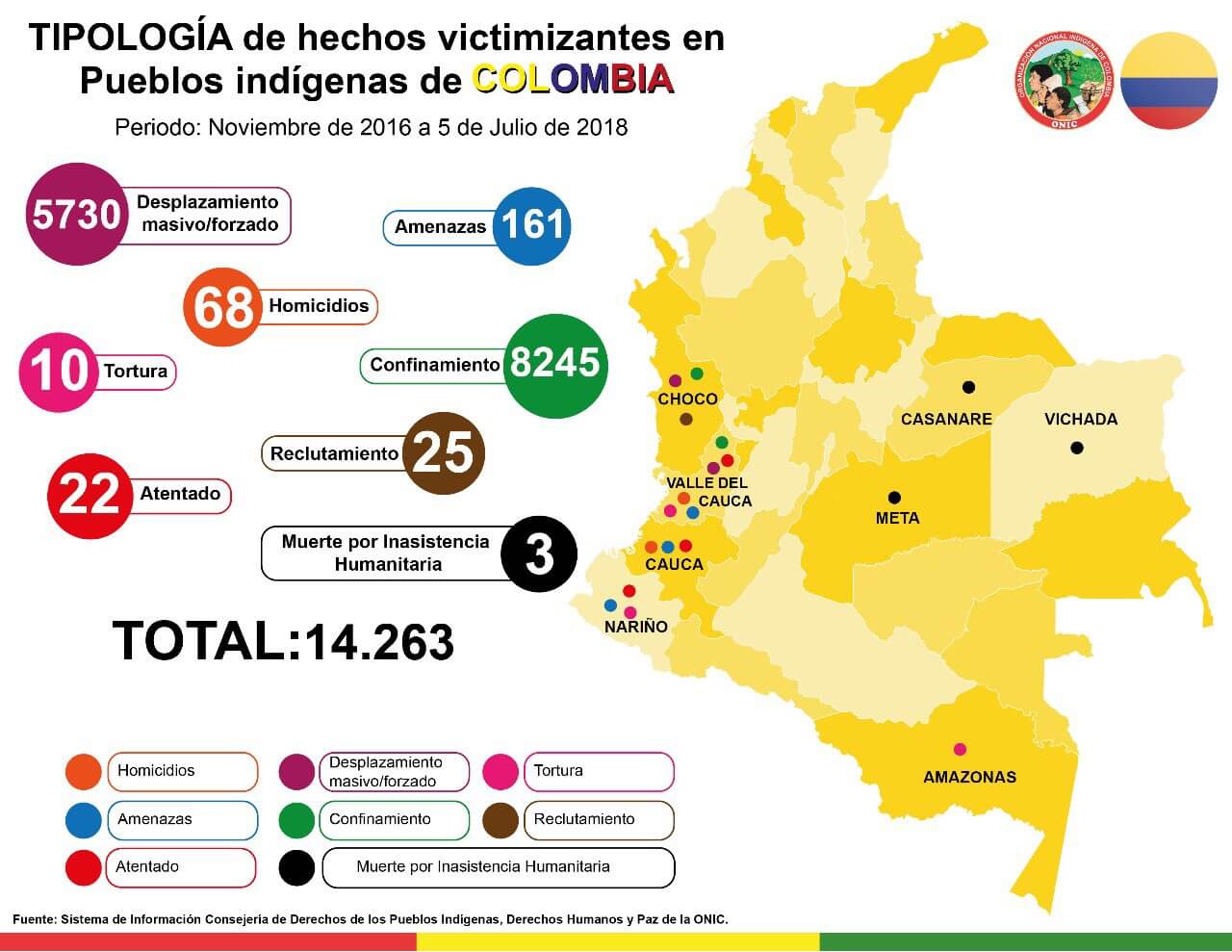

Attacks have hit indigenous leaders across Colombia. According to the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), 68 indigenous people were assassinated between November 2016 and 5 July 2018, while 5730 were forcibly displaced, and 161 received death threats.

Overview of attacks against indigenous leaders. Graphic by ONIC

Overview of attacks against indigenous leaders. Graphic by ONIC

Dilson Borja spoke to IC Magazine before the 24-hour deadline expired: “I was forcibly displaced from the indigenous community of Rio León in northern Uraba due to our work recovering the reservation from the hands of the AUC/Clan del Golfo, groups of criminals which currently organize themselves under the banners of the Black Eagles as well as the Clan del Golfo. We refer to all of them as the BACRIM (bandas criminales / criminal groups). I was displaced with all of my family to the city of Medellin, where I am now the senior indigenous guard of the Indigenous Organization of Antioquia,” he said.

“I’ve been displaced here for a year and a half. Every time that I go back to the territory, to my reservation, I have to be accompanied by various indigenous guards for my protection. Four months ago I was in a human rights meeting in the reservation when I had to escape an attack against my life.

“Then, yesterday, at three in the afternoon, I was threatened by armed men who came to my house and told me that I had 24 hours to leave… The attacks against us come due to the restoration of land for which we are struggling at all hours, and because we are campaigning against mining in indigenous territories. Another reason for the latest threat is due to the support I gave to the candidacy for president of Gustavo Petro,” Borja continued.

“In our page on Facebook we were publishing many news stories about the threats and attacks against social leaders, and just a short while ago I made a video on the theme, and this upset the BACRIM. The current situation in Colombia for social leaders is very worrying; they want to shut us up but you know it would be worse for us to become quiet because the more fear we have the more strength they take.”

Attacks on non-indigenous activists in the last week include the killings on Tuesday (July 3) of Santa Felicinda Santamaría, a community leader in the western region of Choco, and of Luis Barrios Machado, a human rights activist in the northern region of Atlantico who had been refused state protection despite receiving death threats.

On Wednesday (July 4) Ana María Cortés (46), the secretary of the presidential campaign of Gustavo Petro, was shot repeatedly and killed, in the town of Cáceres in northern Antioquia. Cortés had received threats related to her political work, which according to presidential candidate Gustavo Petro included one from a police commander of the region.

In the last week of June, nine social leaders were killed. The explosion of violence (123 activists assassinated from the start of 2018 until July 3) led to large candlelit vigils being held at 6pm on Friday, July 6, in the main squares of towns and cities across Colombia.

Some participants chanted the words of the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda: “You can cut all the flowers, but you can’t stop the spring.”

But the killings haven’t stopped. Two nights ago (July 7), Frank Dairo Rincón, the coordinator of Petro’s campaign, was stabbed to death at a hair salon in the southern town of Pitalito.

The killings of social leaders have increased since the peace accords were signed between the Colombian government and Colombia’s then-largest guerrilla organization, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Criminal groups are now scrambling for control of resources in areas formerly inaccessible due to the guerrilla presence. They are also competing to secure pathways to transport narcotics to the coasts.

The presidential election on June 17 also increased political tensions. Gustavo Petro campaigned on a platform of transforming the country’s development strategy away from mining and energy projects towards reenergizing the agricultural sector. His opponent, Iván Duque, denounced Petro as a dangerous leftist (Petro was formerly a member of the M-19 guerrilla movement before it demobilized in 1990) and insisted that he would prevent Colombia from becoming “another Venezuela”. The choice between a left and right-wing candidate was a novelty in the recent presidential elections that opened up divergences over how the legacy of the civil war would be handled.

Duque is the protagonist of Alvaro Uribe, the right-wing leader who many Colombians credit with seriously weakening the FARC guerrillas, supposedly reducing their numbers from 20,000 to 8,000 by the end of his presidency. While the FARC were reduced in strength and pushed away from the major cities and transport corridors, contemporary research casts doubt on the extent of his successes: over 10,000 civilians were shot by the military during Uribe’s presidency and dressed up as guerrillas to boost “combat kills”. In other words, the majority of the 16,724 “guerrillas” killed between 2002 and 2010 were actually civilians.

Uribe and other powerful figures are fearful that they may be called to account for abuses and war crimes, while the restitution of the 15% of Colombian territory that was seized from its rightful owners by all parties to the conflict also faces powerful opposition.

But while such contemporary dynamics may explain some of the attacks, violence has long been elemental to Colombian politics and economics.

“YOU CAN CUT ALL THE FLOWERS, BUT YOU CAN’T STOP THE SPRING.”

Colombia’s Nobel Prize-winning novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez remembered how political tensions affected his school days around the period of the 1946 presidential election, which while it was “a good period” for his school, it was “the least promising one for the country” due to increased political tensions. In his autobiography “Living to tell the tale”, Marquez wrote: “Only then did I begin to be aware of the country in which I lived. Some teachers who had tried to remain impartial for the past year could not manage it in their classes, and they would let loose with indigestible outbursts about their political preferences. In particular when the hard campaign for the presidential succession began.”

The 1946 campaign saw the Liberal Party split between the establishment’s Julio César Turbay, and the radical left winger Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, who had rallied against the “oligarchy” of a few families that had exercised perpetual control over Colombian politics.

As a result, the Conservative Party, which adopted the colour blue from the Virgin Mary’s robes, won the elections under the candidacy of Mariano Ospina Pérez, with the Hitler-supporting Laureano Gómez pulling the strings in the background. Garcia Marquez continued in his memoir: “Laureano Gómez began to prepare to succeed him by using official forces with all-out violence. It was a return to the historic violence of the nineteenth century, when we had no peace but only ephemeral truces between eight general civil wars and fourteen local ones, three military coups, and then the War of a Thousand Days, which left some eighty thousand dead on both sides in a population of four million people. It was so simple. It was all a common plan for regressing a hundred years.”

Gaitán would be assassinated two years after the 1946 election while Turbay would be elected in 1978 and pass the Security Statute that saw extensive use of detention and torture by military tribunals of suspected guerrillas and guerrilla-sympathizers.

Following Gaitan’s assassination, forced displacement and assassinations spiralled in the countryside as conflicts between left and right accelerated and local powers took advantage to seize land. The very design of Colombian cityscapes today reflects the continued forced urbanization as the displaced arrive seeking work. The testament of one conservative father is typical:

“My grandfather had a good little farm in Salonica near Riofrio in Valle. I was 5 or 6 when we were displaced for political violence; we couldn’t continue to live in the territory because someone from the Liberal Party would have killed us if we hadn’t accepted to be expelled, an uncle of mine was assassinated. So my grandfather had to abandon his farm and we came as refugees to the city of Buga. He had to accept the value that those who displaced him chose, which was 14 thousand pesos, of which he received just seven thousand, which is nothing. In Buga we could only buy a small house and start a small market stall to sell potatoes and panela, which used all the money. In the farm we had had all the community typical of the countryside, all the food, cattle, coffee, we had lived comfortably. In the city it’s not the same: with a small business that can only just cover a little food, and without the same community, it was an abrupt change due to the violence of Colombia, violence caused by the politicians. It was all created by the politicians so that the people would leave for the cities because the people lived comfortably in the countryside whereas here in the cities there were big companies without people wishing to work for them, so this was an idea of theirs so that the campesino people would leave for the cities and work for them on a poor wage. We were part of this violence in Colombia that commenced in the year 1948 and now, when we don’t talk about political violence but the violence of guerrillas and paramilitaries, it is similar to what we suffered.”

Manuel Rozental, a contributor on the Nasa indigenous Radio Pa´yumat, describes the violence coursing through indigenous communities in Cauca as symptomatic of a new phase in capitalism: “We have passed from the forms of neoliberalism and free trade (although they have not ended), and we come to a much more aggressive and harder capitalism, and if we don’t understand this model then we can’t understand the nature of what we call paramilitarism, organized crime, fascism. Capitalism has always been organized crime, capitalism in essence steals from nature its wealth and from people their time, their strength, their work, their intelligence; it steals all of this and turns it into profits for a few.”

Author’s note

While I was finalizing this article, Dilson Borja’s 24-hour warning expired. I received a WhatsApp message from him just after 8pm telling me that the Clan del Golfo was outside his house. He remained hidden and avoided voice messages or calls as they would hear, and we continued to communicate via messages, alerting human rights organizations.

Sadly, such situations would be of no interest to the Colombian media, which has been condemned by the left-wing former senator Piedad Cordoba in relation to the recent attacks:

“Not a single media organization spoke about who Felicinda Santamaria was, they didn’t send teams of journalists to interview her neighbours or family members, nor did the radio speak of her communal work in the neighbourhood of Virgen del Carmen del Choco, not one national media has documented a single case of leaders who have been assassinated, they only report numbers, not a single life story, or something that vindicates what these men and women did; community leaders, indigenous leaders, campesino leaders, that helped their communities and their people.” In the middle of these deaths, she added, all that remains is desolation and indifference.

July 9, 2018